Some 3,000 years ago, a member of a Late Woodland Indian clan traveled far from home on the day's hunt. Darkness fell with the young hunter still several miles away from the other eight members of his band. Cold, clear, water lapped at his knees as he crossed the headwaters of the upper Meramec River by the light of the harvest moon of late fall. The hunt had been unfruitful, but the hunter remained alert. Lights seemed to flash in the crystal clear water. The ancient hunter thrust his stone-tipped spear into the shallow riffle and impaled a wriggling yellow sucker. He, too, would proudly contribute food to the clan when he returned.

|

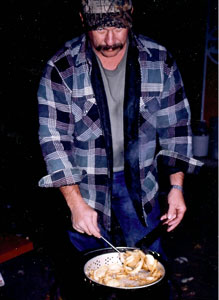

| Spearing fleeing suckers from a moving boat at night is a challenge that requires lots of practice to perfect. Terry Larue is one of the best. |

Spear fishing or "gigging" was common among American Indians. Winter time tactics included the cutting of holes in ice and dangling wooden lures to attract fish within spearing range. Another tactic, which required less skill, consisted of simply watching an open hole in the ice until a fish appeared.

The rest of the year Indians used their canoes and hunted fish at night using torches as a source of light. Usually, a single prong spear was utilized to stick large fish while a three-pronged spear was used for smaller fish. Long, wooden poles tipped with bone, stone or copper were the weapon carried by those fishermen of long ago.

Twenty-first century gigging technology in the Missouri Ozarks is not far advanced from the methods of the ancient hunters. However, gigging seasons now limit hunters to the cool weather months from September 15 to January 31. Although modern day giggers are not compelled to do so to survive, some urge deep in their souls pulls them to Ozarks streams on cold winter nights to gig fish and follow the traditions of their ancestors.

Legendary knife maker Ken Richardson of Dillard, Missouri began gigging in the early 60's. "I remember some of the old timers like Cletus Cottrell of Cherryville, who used to talk about gigging out of long cypress Jon boats. They built pine-knot fires on the front of their boats for light."

Ingenious innovations are the norm for Ozark giggers.

Richardson rocked in his old rocking chair at his daughter and son-in-law's Mountain Man store in Steelville as he continued. "Most guys made their own rigging to hold mantles for light. A piece of shiny metal served as a reflector to angle the light towards the water," Ken laughed again. "Those rigs worked like a charm until you hit a limb. Then you found yourself in the dark!

|

| A hog molly on the end of gig is a welcome sight. A member of the sucker family, hog mollies are a delicacy when fried fresh on the riverbank. |

Gigging had its legends in the old days, too. Richardson told of Jack Ransom from Leasburg who did most of his gigging from the bank. "It was said old jack could throw a gig all the way across the Meramec River and kill a fish," Richardson held.

Riverbank cookouts on the Meramec were standard fare, too. A whole hill community often went gigging together. The atmosphere rivaled that of a fall festival.

Legendary gig makers earned reputations along Ozark streams and were highly revered. Richardson recalled Frank Smith of Sullivan. "Frank was an old blacksmith and horseshoer. In his later days he primarily worked on gigs. He made his gigs out of old spades and pitch forks on his forge. His gigs didn't bend or break. If you had a Frank Smith gig, you had yourself a real gig."

Crawford County residents Charlie Clay and John Halbert remember their dad and grandpa — the same man — Chub Clay. "He made his gigs out of pitchforks and potato forks back in the 50s and early 60s," Clay related. "He used an old forge and approached the job like carving an elephant from a block of wood. He simply heated the metal, beat it out and removed everything that didn't look like a gig."

Chub sold his gigs through local business folks in Steelville like Ken Payne and Ray White. Three-pronged gigs brought $4, while four-prongers bought $6.

Halbert is a modern day gig maker. He cuts his gigs out on a water jet machine that operates at 45,000 to 50,000 pounds of pressure per square inch. 'I use aircraft stainless steel for the prongs," he said. "I cut them out in one piece. Then I thread and weld the shaft onto the gig."

I joined Halbert, Scott Manion and Tommy Porter for a gigging trip on the Meramec River near Onandaga Cave. Porter launched his 20-foot aluminum boat equipped with a 150 horsepower jet drive Mercury engine. A gasoline powered generator produced electricity to operate powerful lights suspended from a rail at the front of the boat. A broad deck at the front of the boat, surrounded by a waist high rail, to keep giggers from falling into the cold water, provided ample room for two people to stand perched with gigs in hand. Porter motored slowly through the holes and riffles while the rest of us took turns stabbing at fleeing suckers. I quickly began to understand the importance of water depth, light refraction and quickness of the gigger. We may have fancier lights and boats than our ancestors, but the method of striking a fish with a long pole with points on the end is much the same.

In every outdoor pursuit there are those individuals who stand out above the rest in every sense of the word; their passion for the outdoors lifestyle, their attention to detail, both of the habits and habitat of their intended quarry and the organization and quality of their equipment is unrivaled by their peers. I spent an unforgettable evening gigging on the Gasconade River with a trio of experienced rivermen.

|

| Cooking up fresh suckers, potatoes, onions and hushpuppies on the riverbank is as much a part of the Ozark gigging tradition as spearing the fish themselves. |

Terry LaRue, his son Lucas and Leroy Dixon, all from Viburnum, invited me to tag along on a gigging excursion. It didn't take long to realize that these men loved the sport. The trio laughed and chattered incessantly as they double checked every piece of equipment before heading up the Gasconade River.

Terry motored up river a mile or so to check things out before darkness closed in around us. Lucas and Leroy selected their choice of gigs from a pile of poles as long as the boat. The pair resembled ancient troops with spears preparing for battle. Less than a minute after the hunt began, Lucas leaned precariously far out over the gigging rail and jabbed at a fish. I sat flabbergasted that he came up with a wriggling yellow sucker. I had never seen anyone thrust a gig at a fleeing fish that far away!

The guys insisted that I take a turn at the rail. Fortunately, Terry had just mentioned that he had a terrible time hitting doves with a shotgun. Ten minutes into my turn at the rail I quipped, "You know, Terry, I am a darn good dove shot." Laughter rocked the boat creating weird shadows in our small halo of light.

Terry and Lucas exhibited exceptional boat handling skills, learned by many nights on the water. Each kept a sharp eye out for fleeing fish in front of the lights and quickly sped up to put the giggers on the fish. More phenomenal was the ability the trio demonstrated at sticking fleeing fish from a boat that clipped along at 10mph!

After collecting 65 yellow suckers, hog mollies and red horse — all varieties of the sucker family — we beached at the put-in point to begin cleaning our catch. The limit for suckers is 20 per person. We were allowed 80. The one person who fell short of a limit took a terrific bunch of ribbing from his fellow giggers. There is no mercy among modern day giggers.

The trio moved about on shore like a small colony of ants. Five-gallon buckets, knives and old ironing boards lined the banks in the shadow of the gigging lights on the boat. My interest peaked at the introduction of the ironing boards. I figured I was in for a real hoax! An assembly line formed. Three of us scaled fish while the fourth filleted fish with an electric knife. The old ironing boards made the perfect fish cleaning tables. The chore fell before skilled hands in a matter of minutes.

We moved up the bank to a picnic table to begin cooking. Terry removed the rib bones from the fillets, while Lucas, Leroy and I scored, or cut, the flesh to the skin. The cuts were made a quarter-of-an-inch apart. That allows the flesh to cook quickly in hot oil. And any bones left in the meat are rendered edible. We feasted on mounds of steaming sucker filets and fried potatoes, hushpuppies and onions. My watch read 11 p.m.

"Gigging is a real social event," Terry reasoned. "We love it. We have been at it a long time. It is a family tradition that we hope to pass on."

Gigging an Ozark stream is an age-old Ozark tradition, one that I hope continues for a long time to come. Laughter on an Ozark stream on a cool fall evening, enhanced by the lights of a gigging boat, is medicine for the soul.

If only Larue could meet the Indian who speared the sucker on the Meramec by the light of the harvest moon. Stories would flow like the river itself!

- 11762 views